If you missed our first post in this series, read it now.

Warehouse Experiment - UPDATE

A little over a year ago, we shared a post on the ISC Barrels blog about a warehouse experiment we started with Willett Distillery back in 2019. In that post, we discussed the 12-month chemical data for composite samples of floors one through five and conveyed our conclusions from the information we obtained. Click here to revisit the original post.

It is hard to believe but this experiment will be coming to an end this September. Being that the four-year summation is just around the corner, I wanted to provide a brief update using the 36-month chemical data we obtained from the samples; if only to show you something we did different this year with the sampling.

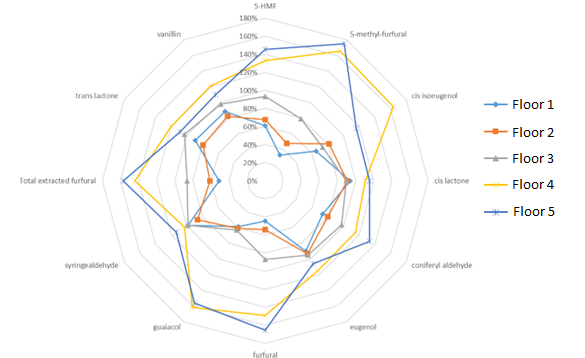

First, let’s review the 12-month results for each floor. The data is displayed below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. 12-month Chemical Data

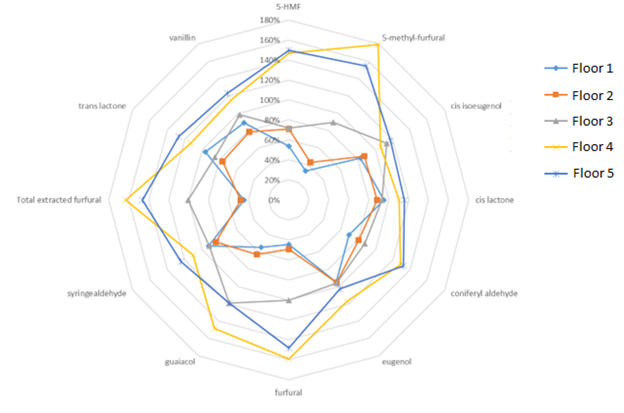

If we compare these results to that of the 36-month samples (displayed below in Figure 2), we can see a couple of things.

Figure 2. 36-month Chemical Data

First, let’s note that the flavor profiles for each respective floor remained relatively unchanged between 12 and 36 months. When utilizing non-toasted barrels, this type of result is fairly consistent.

Second, when we summed up concentrations for all key flavor congeners at 36 months, we found that Floor 1 was the least extracted; followed by Floor 2, Floor 3, all the way up to Floor 5. This is also consistent with the data obtained from the 12-month samples. We can make some additional conclusions, but I will save that for the experiment summary after the 48-month data is collected.

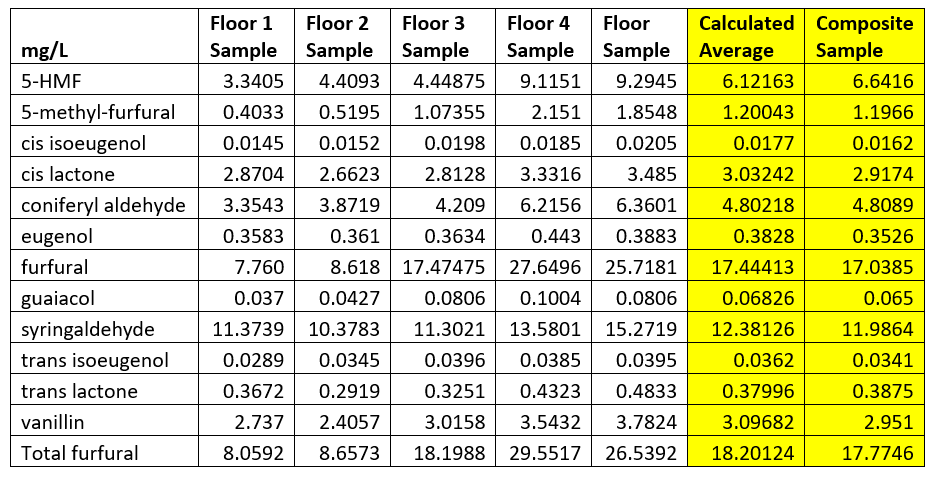

We made things more interesting by taking the 36-month samples and creating one composite sample of all five floors. First, we composited the six barrels from each floor to get our individual composite sample for each floor. We then took a 50mL from each of the floor composites and blended them to create an overall composite for all five floors. The data is displayed in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Concentration Comparisons to Composite Sample

The nice thing that occurred here is that for every compound measured, the calculated average concentration across all five floors differed from our overall composite sample concentration by an average of less than 1%. Some might say this a stretch to call this interesting or unexpected, but I found the results to be quite satisfying. Maturation chemistry is very complex and more often than not, you run across unexpected results when conducting different experiments. Sometimes this is due to instrumentation error; sometimes there might be an error in compositing; and sometimes the results are correct but totally unexpected!

The result from this little test doesn’t represent any kind of unknown phenomena or strange outcome. It was just a nice occurrence where things seem to uncomplicate themselves and behave exactly as you had expected. And in my job, that is something to shine a little light on. Hope you enjoyed it!

Cheers!

Andrew Wiehebrink

Comments 2

Andrew, Sometimes data is collected just for the sake of collecting data…. I can see how you are quantifying a mystery leading to further understanding the art of seasoning whisky.

I am particularly interested in the impact of the staves from different trees or areas of growth on the process and flavor profiles.

Are there any scientific results of the Maker’s Mark experiment that resulted in 46 being chosen?

Tom Mereen

Doug Sammons

Andrew as a retired biochemist and woodworker I find your data and efforts interesting. As I study the concepts of extractives it seems to me very little is done to optimize the process and worse there are no clues to target levels for an optimized predictable reaction course. The barrel is a “chemical reactor”, hence the reagents (extractives), reaction conditions ie., pH, temperature, ethanol concentration (and in particular methanol and acetic acid) and oxygen levels should all be at least be bracketed to define a known starting condition. As a discovery research scientist for 40 years I can tell you for certain, that ill defined systems will only randomly yield a positive result and will still be difficult to reproduce or control. However, in practice, it’s obvious that simply loading a barrel and waiting works often enough to provide a product that can be used and/or mixed and sold, maybe that is sufficient for some. I would rather see us (collectively) make exemplary mixtures reliably. I see at least 3 particular starting conditions. The oak; staves are much harder to control extraction then spirals or chips etc., and the degrees of toasting of different oak samples to yield similar levels of key extractives and measurements (characterization ) of the first extractive blush (the major amount?) and it’s composition. Secondly, the new make spirit should have a defined amount of organic acids, long chain fats, esters if present already etc., that at least allows us to know what will react. Finally, the actual preferred ester chemical reaction conditions (along with other reactions) defined by H+, temperature, oxygen available etc,. By controlling the more predictable reactions we can refocus on steering the minor reactions . The GC/MS is the way to go with sampling methods that do not create new conditions. As an old man now I definitely am interested in finding ways to speed this whole process up.

Good work,